The Turn of the Screw

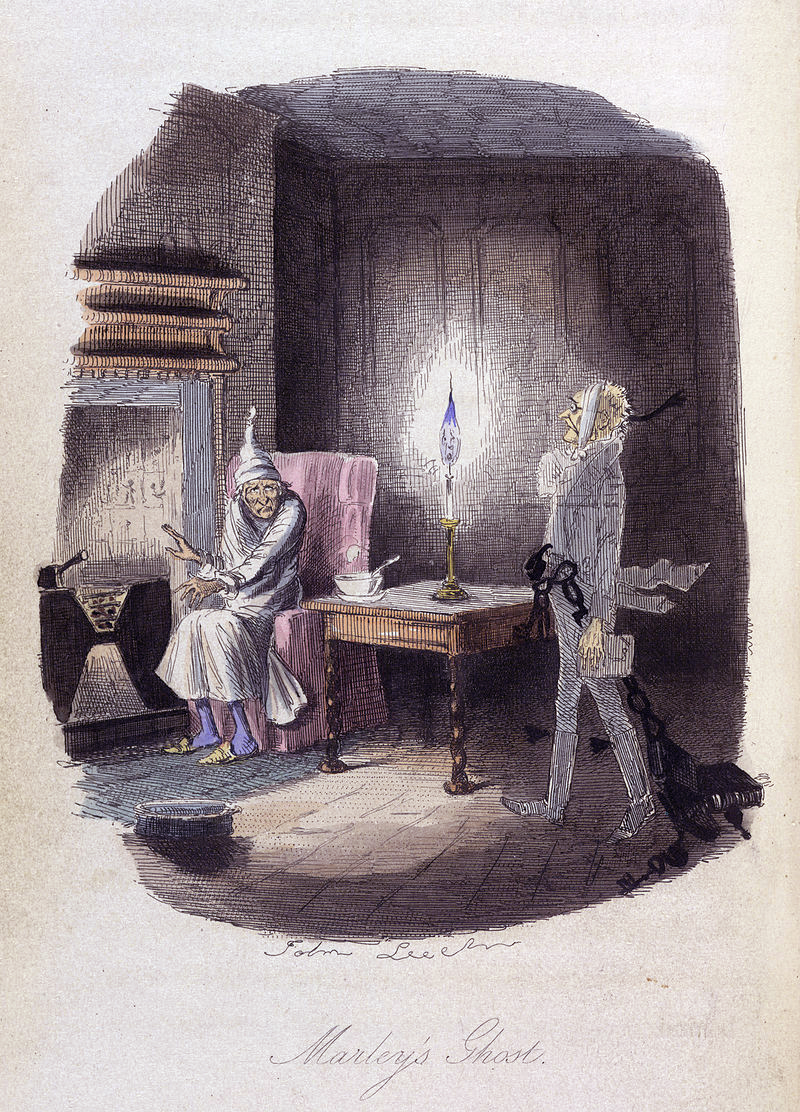

The Turn of the Screw is a ghost story by Henry James, which was originally published in 1898. The novel opens with a group of friends who are telling ghost stories. After hearing a ghost story involving a child, a man named Douglas proposes to tell the group a true story about two children. Douglas asks the party to wait for a manuscript to be delivered to him. He explains that the story was written by a woman who was once his sister’s governess and that it describes events in her life. Douglas was in love with the governess. She is now dead, but members of the group realize that Douglas still has strong feelings for her.

Days later, the manuscript arrives, and the story begins. The entire story is told from the point of view of the Bly governess. Because of this narrative construction, the reader must evaluate the honesty of the story. It reminded me of the narration of Emily Bronte’s

Wuthering Heights.

The governess takes a job caring for two children at Bly. The one condition of her job is that she must never speak to the Master of the house about the children, who are his niece and nephew, Flora and Miles. The governess agrees to these bizarre conditions and falls in love at first sight with the Master. She befriends Mrs. Grose, the housekeeper.

When ten-year-old Miles is expelled from school, he joins his eight-year-old sister at home. Soon, strange events begin occurring. The governess sees two ghosts, Peter Quint (the former gardener) and Miss Jessel (the former governess). The governess takes it upon herself to protect the children from the ghosts and believes the ghosts and children are communicating with one another. But through her actions, will the governess help or hurt the children?

I think the greatness of this story is how mysteriously vague it is. It left me with so many questions. Is the governess crazy? Are the children crazy or possessed? Are there really ghosts? When the governess speaks to the children, do they know which "he" and "she" the governess is asking them about, and vice versa? I wondered if the characters understood one another, and how much of the conversations were one-sided. The governess makes many presumptions. For instance, she never asks why Miles was expelled from school. At first, the governess believes Miles is an angel and then she later thinks he’s a demon, but how much did the boy’s behavior really change?

Looking back, most of the motivations, especially those of the children are coaxed. For instance, at the lake, is Flora really possessed and ugly, or is she just scared of her freakish and unrelenting governess? The children may be biding their time until their Uncle arrives, thinking that the governess mails their letters and that he's busy. Meanwhile, the governess has hoarded their letters.

I wondered how the governess identified the ghosts. Mrs. Grose recognized Peter Quint upon hearing his description, but the governess pounced on the idea and furthered it rapidly. The governess also leapt at the idea of Miss Jessel being one of the ghosts with little rationale. One thing that I found odd was the episode involving crying on the steps. The governess first sees Miss Jessel cry there, and later she cries in the same location. What did this repetition mean? Was it to show how similar Miss Jessel and governess were in temperament and position, or did it serve some other purpose? Is Miss Jessel simply the governess's idea of herself or what she could become?

The governess's love of the Master is also inexplicable. Does she truly feel his love is reciprocated through his disinterest? Does Mrs. Grose understand that the governess is in love with the Master? In addition, the governess was so worried about Miss Jessel and Peter Quint controlling the children, but she did the same thing. The governess was definitely strange, but it's impossible to argue that the children were not. They were equally strange.

In the closing scene, did either Miles or the governess name Miss Jessel? I wasn't sure who said it. The use of "he" and "she" leave almost any scenario possible.

After I finished the novel, I came up with a strange idea in trying to connect the prologue to the main story. I began wondering if Miles was really Douglas and if Miles did not die at the story’s conclusion. I went back to the prologue and re-read it. I was surprised that there was no return to the story-telling group at the end of the story, and instead, the tale just ended. Douglas's description gives the impression that he was in love with the governess, putting his impartiality into question. He mentioned that the woman was his younger sister's governess, which made me wonder if his younger sister was Flora and if he was still-alive Miles. Of course, I may be over-reaching. The main purpose of the prologue may have been to put distance between the reader and the governess, and the use of the manuscript could have been a contrivance to tell such a long story.

Another thing puzzled me about the governess. After such a horrid experience, would she really want to seek a new position as a governess ever again? I surely wouldn't. I wonder also at the conditions the governess agreed to. She committed to go to an isolated house and raise two children she had never seen without ever being able to contact their only relation. Why would someone agree to that?

In reading theories online, one reader said that they believed that Mrs. Grose was in fact the children’s mother from an affair with the Uncle, and that the governess had taken control of the children from their mother by making her inferior in her own home. Stemming from this, it was suggested that Mrs. Grose was conniving to make the governess mad by planting ideas in her mind. Though I did not see this during my reading, I thought it was an interesting take.

The Turn of the Screw is one of those books that leaves you with many questions and an eerie feeling. It’s the type of book that demands re-reading.

Related Reviews:

Daisy Miller by Henry James

The Aspern Papers by Henry James

Purchase and read books by Henry James:

©

penciledpage.com

Search This Website